What Preaching Is Not

In our current (Easter) print issue, my Liturgical Observation column provided an analysis of preaching, and some common preaching practices that cannot even legitimately be classified as preaching. The article is posted here, in hopes that a wider discussion of these matters can be generated, toward the hope that in the end, better preaching might be result.

It’s not a malady of our times only that so much of what passes for preaching is nothing like what preaching is meant to be. Martin Luther lamented the dearth of good preaching so much that he wrote his Postil as a remedy,

in order that the Christian people may hear, instead of fables and dreams, the Words of their God, unadulterated by human filth. For I promise nothing except the pure, unalloyed sense of the Gospel suitable for the low, humble people. But whether I am able to accomplish this, I shall let others judge. Empty opinions and foolish questions, which are of no value, no one can learn from use.[1]

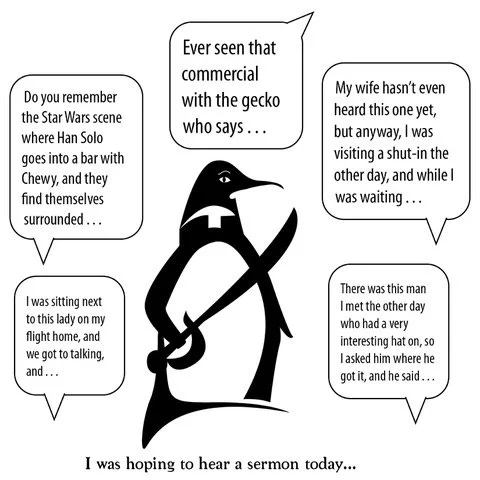

It is nonetheless lamentable that, in spite of the superior access preachers of our day have to good homiletical training and books, there remains a heavy dose in our pulpits of fables and dreams, at least if we are to believe the abundance of anecdotal evidence hear reported from others on a regular basis, which tends to agree with what we ourselves have seen. Sermons, alas, have as their standard fare an abundance of extended stories and vignettes from the personal life of the preacher or from other equally banal sources, all of which are said to be somehow in service to the Gospel they are employed to portray. The sermon routinely begins with such a story, and sometimes the opening story consumes several minutes of the preacher’s time. The Biblical reading on which the sermon is said to be based might not come up until he’s well into the time given to the entire sermon. Preaching should not consist in extrabiblical stories and casual banter, but should be reverent and filled with Scripture. It should be crafted in a way that can rightly be called preaching the Gospel.

But the preacher whose default opening is an extrabiblical story must then explain the story in a way that shows the hearers just how the Gospel is somehow represented in it. Sometimes, I suspect, the preacher has latched onto some such account in search of a way to use it, in which case what drives the choice of a message is the story, especially when it is perceived to be attention-getting or interesting in its own right. And if this is true, it can only mean that the choice of the message is not driven by the appointed reading on which the sermon is supposedly based. Hence, in the end, the pastor is technically not preaching on a biblical text at all, but on his personal or received story.

Just how did this practice become so ubiquitous? If we compare, say, the sermons of Martin Luther, or of St. Augustine, or of some other early Church Father, we see no such stories. Rare is the evidence of anything personal from the life of the preacher entering into the sermon. What those sermons are filled with, by contrast, is the preacher’s explanation and application of the material he finds on the sacred page.

I have long believed that the best way for a young pastor or seminarian to begin to learn how to preach is simply to read some of those sermons for himself. Luther’s Church Postil, for example, is widely available, and one of the finest resources for a preaching example to emulate. Augustine’s sermons are also easy to access for this reason, as are other well-known fathers of the faith. Additionally—or should I say, concurrently—what is essential for a preacher to have at the ready is a rich awareness and knowledge of what’s in the Bible. I can’t help but wonder how much of the epic failures of too many sermons is simply due to a failure on the part of preachers to have a steady course of Bible reading for their own enrichment.

Whatever the cause, there does seem to be a lot of preaching going on that demonstrates all too well what preaching is not. What too many preachers tend by and large to do is bypass all this rich material and seek to fill their sermon with material from the impoverished sources of their own experiences or those of others.

Which brings me to the “Craft of Preaching” section at the 1517.com website. It’s a very convenient resource for preachers, which turns out ultimately to be unfortunate, because it, also contains questionable material mingled in with what would otherwise be acceptable: leaven, that is, in the sense that I called attention to so much of what’s found at 1517 last year.[2] In fairness, I have to add that in this case it seems to be simply part of a much larger problem in many churches rather than the cause of it. That is to say, 1517 has no corner on this particular problem, because it’s quite common, at least in the LCMS. This is a preaching problem. What’s disturbing about 1517 in this regard is that the homiletic material they provide is on the one hand plentiful and in many ways helpful, at least in terms of links to resources, and on the other hand given to a fundamental misunderstanding of what preaching is. So, more leaven. In this case I’m picking on 1517 mostly as an example of the difficulty.

But the site does seem to have some very attractive suggestions and insights dedicated to making sermons better, at least at first glance; and lots of resources right at the preacher’s fingertips, including materials for each week of preparation: articles, videos, and podcasts dedicated to helping the pastor prepare his Sunday sermon.

There are also helpful links, some of which are to Concordia Seminary in St. Louis and Concordia Theological Seminary in Fort Wayne. “Lectionary Kick-start” contains podcasts of weekly discussions with Dr. David Schmitt and Dr. Peter Nafzger, professors of homiletics at Concordia Seminary, Saint Louis. The “Lectionary Podcast” routinely links to lectures from a number of professors at Concordia Theological Seminary in Fort Wayne.

The “Preacher’s Toolbox” sub-section—evidently so named because it has to do with how to craft a sermon—contains articles by one Ryan Tinetti, an LCMS pastor at Trinity Lutheran Church in Arcadia, Michigan. Pastor Tinetti has a D.Min. from Duke University in homiletics, and here he discusses the preparation of sermons and preaching method, aiming at making pastors better preachers. One article discusses the importance of preaching with conviction and opposes “blathering” in the sermon. I especially like this part.

Do not take the time in the pulpit for granted. . . . Preach, that is, like your life depends on it. Or more to the point: Preach like your hearers’ lives depend on it... because they do.”[3] Well put, I’d say. Another article favorably discusses the gradual process of preparing a sermon patiently: ”get everything down on paper: Exegetical insights, potential illustrations, insightful quotations . . . all of it. Cannot figure out whether it fits, or where yet? That is okay. It can get chopped later. To paraphrase Hemingway’s famous adage, you can often tell the quality of the preacher by how much is left on the cutting room floor.[4]

So far, so good.

But then comes the problem. I read Tinetti’s thoughts on storytelling, which he has laid out in a three-part series. He starts by making a good case for it. While steering preachers away from being trite, he argues, “The Lord Jesus is the consummate preacher and He preached in stories, so you should too. . . . [F]or those preachers who eschew stories, the onus is on them to justify why we should not in some modest way follow Jesus’ example.” Further, “God the Father is constantly relating stories (lower-case) in the Scriptures, even as all of time bears the stamp of His Story (upper-case). This is the core insight of narrative theology: The Bible is story-shaped, God’s modus operandi is narrative, and ultimately the arc of history bends toward ‘happily ever after.’ Small wonder, then, that when preachers use stories, they get the attention of God’s people.” And finally he adds, “let me also stress one reason not to use stories, namely, as window-dressing on an otherwise drab presentation. This is the ‘Insert Reader’s Digest Anecdote’ school of sermon illustrations, and it is a lame excuse for storytelling.”[5]

So Tinetti is using stories to “get the attention of God’s people,” and to “facilitate memory” because they “possess their own inner logic, which makes moving from Point A to Point B relatively effortless.” They are also “inspirational” and “an essential way not only to motivate our hearers to act on their faith, but to help them imagine how to act.”

But here’s where the presentation takes what I’d call a sharp turn down a dark alley. Tinetti makes suggestions for where to find worthy stories. They are, he says, “all around us.” He offers “storytelling podcasts such as This American Life and Radiolab, history books (especially biographies), the sermons of other preachers you admire, and even the ministry booths at the pastor’s conference.” Then he gets into personal visits the pastor makes as a good source for stories he might use, whether stories about the visit itself or stories he hears from the people he visits.

Ah, here we go. Here come the very stories I’ve been lamenting, the pablum filling the ears of the hearers. Why, oh why do we have to hear these? Aren’t the Bible’s stories enough?

Apparently not, even though, remarkably, even Tinetti eventually gets around to suggesting the use of Bible stories. He evidently thinks they’re just part of the treasure-trove of “stories all around us” that capture the minds of the hearers. At least when he does get to this part he says something worth repeating:

There is so much material in the Scriptures, not least in the Old Testament. There are stories of terrible sinners being brought to their knees, narratives of super-natural encounters with God, and accounts of love shown to the loveless. The Scriptures are not drawn on nearly enough for their stories. It is as though they do not “count” or some such thing. Early and medieval preachers had no such scruples. In fact, biblical stories, along with stories of the saints, were often their go-to source.[6]

But then, even having said this, and almost as if to disagree with himself, he goes deeper down that dark alley of suggesting other sources, moving away again from the Bible. He ends by suggesting the use of gripping parts of good movies, of all things.

This led me to wonder whether what the fundamental problem in preaching stems from is a rather dramatic difference in understanding just what a sermon is.

Preaching is not simply public speaking. It isn’t like Ted Talks. It isn’t the stuff of motivational speakers. Without a doubt there are many similarities, but we are dealing with two entirely different genres of speaking. Preaching has to do with God’s Word, or rather, to put the matter radically, preaching is itself God’s Word. This is how the Small Catechism puts it, in the meaning of the Third Commandment: “We should fear and love God that we may not despise preaching and His Word, but gladly hear and learn it.” Preaching, unlike all ordinary forms of public speaking, is holy. The explanation to the Third Commandment actually places “preaching” before “His Word,” which clearly implies that preaching is the Word of God itself on the lips of the preacher. Preaching is not, that is, merely talking about the Word of God. It is itself the Word of God. Since this is so—or at least, ought to be so—the preacher does well who binds himself very closely to the Scriptures in the crafting of his sermon, since obviously the preacher’s own thoughts or expressions are not in themselves the Word of God. The sermon is the Word of God in a derived sense. It is the Word of God in so far as it agrees with and proclaims the message of Scripture, and therefore the faithful preacher will want to move from this quatenus understanding of his sermon to a quia understanding of it as clearly as he can: he will want to be able to say that his sermon is the Word of God because it agrees with and proclaims the message of Scripture. Since this is so, he ought never stray too far from the very words and content of the Scriptures even as he seeks to apply the day’s Gospel to the lives of the hearers. To be sure, he is using his own words as he speaks, but the resources he uses in crafting his message should be biblical. So, does he want to embed a story at some point? Fine: let him find one in the Bible.

And about those Bible stories, since preaching is the delivery of God’s Word, and since God’s Word is not only the message of the Bible but the Bible itself, therefore we really ought to be understanding and using those stories differently than we understand and use other stories. The stories of the Bible actually are bound to the message of the Bible intrinsically. Here we begin to see a different measure for adjudging what would constitute good preaching.

I suspect the difference is somewhat lost on so many preachers. Tinetti’s series on stories would presumably be as valuable to someone preparing a secular motivational speech as it would be to a preacher. This indicates a difference in understanding what a sermon is and, for that matter, what the Scriptures are for. They are written for our learning, as the Apostle declares.[7]

The Scriptures are not drawn on nearly enough for their stories. It is as though they do not “count” or some such thing. I didn’t write that; he did. So why must the Scriptures be cut down to one source among many for their stories? If biblical stories were often the go-to source of early and medieval preachers, shouldn’t they be ours as well?

The Scriptures contain a great many stories for us to use, and indeed, I repeat, intended for us to use, in bringing to bear the truths of our salvation. Why, then, must we import extra-biblical stories to fill up the premium time allotted for the preaching of the sermon? Herein lies a major problem with so much of what passes for preaching these days. We’ve all heard sermons full of stories, vignettes, and narratives from modern life, personal life, or even imaginary life. Sadly, the phenomenon is widespread. All too much sermon time is taken up in telling such stories, whose only real benefit for faith might be in their being illustrations of some truth the preacher is trying to get across. It’s such a waste, especially when what we have in Scripture is a treasure-trove of stories written precisely to teach us heavenly truths. Here we have a captive audience, and far too often what they get is some unworthy story they might or might not remember.

I find it ironic that while we at Gottesdienst have been consistently calling for a return to the historic lectionary, the proponents of the three-year lectionary (which, I note, the 1517 resources exclusively use) have given as one of their chief arguments the notion that it allows for the people to hear more of the Bible. Our own Evan Scamman has recently debunked the thinking behind this notion rather decisively, pointing out that the lectionary was never intended to cover a large swath of the Bible, but rather “the whole of salvific history, teaching the faith through repetition, hiding the core tenets of Christian doctrine deep within the heart, helping us to order our comings and goings around the life and death of Christ.” Thus, “instead of asking, ‘Does it have more of the Bible?’, we should have asked, ‘Does it more effectively teach of Christ and His saving work?’” And for that matter, he points out, “Ironically, the answer to this wrong question is that the historic lectionary, which includes a large number of mid-week occasions, covers slightly more of the Bible than the three-year lectionary.” [8] What adds to the irony is that much more of the Bible could easily be covered, if that is truly a concern, in the sermon itself, if only less of the extra-biblical storytelling were to go on. The very argument of the three-year lectionary proponents can be used more profitably toward encouragement for the preacher in the crafting of his sermon. The sermon that is saturated with the Bible certainly provides the hearers with more of it than the sermon that wastes their time with extended illustrations and stories that range from the banal to the clever, notwithstanding the extent of cleverness an extra-biblical story may have. Why do we have the Bible if not to be used? These things were written for our learning. Ok, then, let’s learn from them.

The use of an extra-biblical story has much to do with its attention-capturing, memory-facilitating, or inspirational capacity, but the value of Bible stories is deeper. These stories are generally written not merely as historical records, but as being part of the overall theological narrative of Scripture. And as such they are, in a way, tailor-made to teach divine truth.

Take, for instance, the narrative of David and Goliath. Of course, it can easily be used to illustrate Christ’s defeat of the devil, but the reason for this is that it was intended from the start to illustrate this.

The LCMS endured a theological battle of epic proportions over the historical-critical method of Bible scholarship that reached its climax in the walkout at the St. Louis seminary exactly fifty years ago. Thankfully the Synod came away from that battle with a widespread belief and confession that the historical accounts of the Bible are all factually true and without error. But a casualty of that war was a resultant widespread failure to understand that the historical accounts of the Bible are also illustrative. What emerged was a false dichotomy: either what we see in David and Goliath is historical narrative or it is in some sense a story meant to teach a lesson, and since the latter choice sounded too mythological, it had to be rejected. But this fails to grasp the fulness of the power of God, who is quite capable of arranging history itself in such a way that it teaches a story. Put another way, Aesop used fables, but God uses the course of history as He Himself arranges it.

So we see in David a shepherd boy who puts off Saul’s heavy armor and goes out bare-breasted, a biblical illustration of Christ’s state of humiliation. We see him kill the giant with one stone, another biblical illustration, of the unity of Christ the Rock of our Salvation, or the unity of faith. Our editor Karl Fabrizius has had a regular feature in this journal for decades that is dedicated to finding the meanings embedded in the stories of the Bible. We must not be shy about using the Bible this way but will do well, rather, to see that this is the way it is meant to be used.

This is part and parcel of understanding the sacred nature of the enterprise of preaching. The purpose of preaching is to edify and build up the hearers in faith by the Gospel. And since this is so, we should bear in mind that the Gospel is in words, the Words of God.

What is not helpful, in this regard, is a mentality that is geared merely toward getting and keeping the hearers’ attention. If the use of storytelling only goes that far, then it is misplaced. The list given by Tinetti that inserts Bible stories as one source among many for story selection makes perfect sense if the purpose is merely transactional, toward reaching and keeping the hearers. But that is not the purpose of Bible stories. Rather, again, the purpose is our learning, [9] or, as the Evangelist puts it “that ye might believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God; and that believing ye might have life through his name.”[10]In a more general sense, then, we do well to see that the task of the preacher undergoes a fundamental shift when he sees his own place in the divine process of driving faith into the hearts of the hearers as the Spirit reaches them with the Word of God. Now he takes the mantle of teacher in the same way that the Apostles themselves took it when they received it from the Lord. The difference, of course, is that his teaching is dependent on theirs, as they alone are necessarily without error, and their teaching is the Word of God in an immediate sense. But when the preacher today faithfully carries out his duty, insofar as he is faithful in doing this, his words are just as much the Word of God as theirs. Hence the order of terms in the meaning of the Third Commandment.

For this reason, the small-talk, or bantering, or various attention-getting devices, should not fill the air during the sermon. In much the same way that we at Gottesdienst insist on reverent behavior during the conduct of the ceremonies of the Mass, so do we and must we insist on reverence in the sermon. The sermon in our churches is too often lowered and bowdlerized and transformed into something less than the Word of God.

Put another way, preaching is not to be understood as casual talk. It differs even from the kind of talk that is standard in Bible classes or catechesis. The classroom setting differs from the pulpit, as most of us are instinctively aware. The pulpit is in the holy place; the classroom is not. Hence the classroom can be where bantering, conversing, and joking may seem appropriate, even when teaching the faith. But when the pulpit is used that way, it can have the effect of portraying the setting as common or profane, as opposed to what it is: the Divine Service is a holy setting in a holy place.

If this distinction is not maintained, the result will invariably be a cheapening of the sense of holiness that must accompany all of divine worship. While the sermon is called the Word of God in a derived sense, whereas an Apostolic writing is the Word in a primary sense, there is an nonetheless an essential unity with the apostolic mind-set that the preacher should seek. The Apostles wrote what they remembered and understood from Jesus, and their remembrances were guaranteed by the Spirit. And while no preacher today has any such guarantee, still the activity is essentially the same. And there’s nothing casual about it.

But sadly, here too, there’s often a disconnect. Sometimes the liturgy is carefully followed, except when it comes time for the sermon. Suddenly casualness becomes patently operative. Everyone relaxes. It’s time for the sermon, the “talk,” the stand-up act.

But this mode of preaching was never in evidence in the case of the early church’s preachers. Even seen from the perspective of the words of extant sermons, we find routinely that the language and grammar of the Scriptures are incorporated. And in this they mimicked the approach of the apostles themselves. The epistles of St. Paul and St. Peter are found likewise incorporating the words and word patterns of the Scriptures in their apostolic communications.

As it happens, the current state of preaching is also a lament of Concordia Seminary’s homiletics professor David Schmitt, whose “Lectionary Kick-start” podcasts are referenced above. Schmitt notes the changes in our culture have resulted in changes in the way the preachers and the hearers view sermons.

The Scriptures become a collection of stories of various people who have sinned and been forgiven rather than a coherent revelation of the story of God. We see and identify with individual stories but miss out on the larger story of God. God suddenly becomes a supporting actor in our stories, helping us with forgiveness, rather than one who brings us into his story, taking us as individuals and forming us into a people, his people who have a purpose and live by his proclamation in his world. Suddenly, preachers are taking God and making him relevant, fitting him into our small human stories, having him meet our fragile needs, rather than proclaiming how God makes us relevant, taking us into his kingdom and giving our lives purpose in his world that lies beyond our fallen imagination and is yet to be revealed.[11]

What needs recovering, in short, is a better understanding of what preaching is and what it is not. It is a holy activity; it is a divine activity. It is not a mere motivational speech. And just as we say that we are saved by grace alone, so ought we to say that preaching is made holy when it is the Word of God alone on our lips.

So, on behalf of all the faithful hearers who really do want and need to hear the Word of God from the preacher, but who maybe don’t have the heart to tell him that he’s been wasting their time with his little vignettes, however clever they may be, I’ll say this: We really didn’t come to church to hear your personal stories. What we came to hear is the Gospel. What we need is the Word of God. Just give us that. I could as well say this with the words of a rather simplistic Sunday School hymn I learned at about eight years of age:

Tell me the stories of Jesus I love to hear;

Things I would ask him to tell me If He were here:

Scenes by the wayside, Tales of the sea,

Stories of Jesus, Tell them to me.

[1] Sermons of Martin Luther, vol. 1, edited by John Nicholas Lenker (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1988, a reproduction of The Precious and Sacred Writings of Martin Luther, vol. 10, Minneapolis, Lutherans in All Lands, 1905), 11.

[2] See my “The Leaven of 1517” in the Michaelmas 2023 issue of Gottesdienst, or online at https://www.gottesdienst.org/gottesblog/2023/10/12/the-leaven-of-1517.

[3] “Smart Brevity: Saying More by Saying Less,” https://www.1517.org/articles/the-preachers-toolbox-smart-brevity-saying-more-by-saying-less.

[4] “Seeding the Sermon,” https://www.1517.org/articles/the-preachers-toolbox-seeding-the-sermon.

[5] “The Value of Stories,” https://www.1517.org/articles/the-preachers-toolbox-the-value-of-stories-2023.

[6] “Finding Gold-Sources of Stories,” https://www.1517.org/articles/the-preachers-toolbox-finding-gold-sources-of-stories-2023.

[7] Romans 15:4.

[8] “Guaranteed not to Turn Pink,” Gottesblog, January 9, 2024 (https://www.gottesdienst.org/gottesblog/2024/1/8/guaranteed-not-to-turn-pink).

[9] Romans 15:4.

[10] St. John 20:31.

[11] Richard Caemmerer's Goal, Malady, Means: A Retrospective Glance David R. Schmitt (CTQ 74 [2010] 23-38), 36.