Respect the Genre

My wife and I are seeing Joe Bonamassa in concert with friends this evening, and I am thrilled. I’ve been a fan since discovering his Black Rock album in 2010, and he’s only continued to get better and better since then. A consummate blues rock guitarist, he is a master of his craft at the top of his game. Already in 1989, at the tender age of twelve years old, he opened for and played with B.B. King, who said: “This kid’s potential is unbelievable. He hasn’t even begun to scratch the surface. He’s one of a kind.” In the thirty years since then, Joe has released thirteen solo studio albums and seventeen live albums, four albums with Beth Hart, and five with Black Country Communion (his band with Glenn Hughes, Jason Bonham, and Derek Sherinian). His most recent album, Live at the Sydney Opera House, released just two weeks ago, is a beautiful demonstration of his astonishing musical talent.

Joe Bonamassa possesses plenty of natural ability, but he’s also worked hard to develop and hone his skills. In spite of early recognition of his prowess on the guitar, he struggled for many years to catch a break in the music business. His recognition, success, and all but five of his many albums have come within these past thirteen years, since 2006. He’s not relied on the record companies or radio airplay but on prolific creative output and persistent touring around the world. Album by album, he’s slowly been making his mark and earning his fans. He’s also learned along the way.

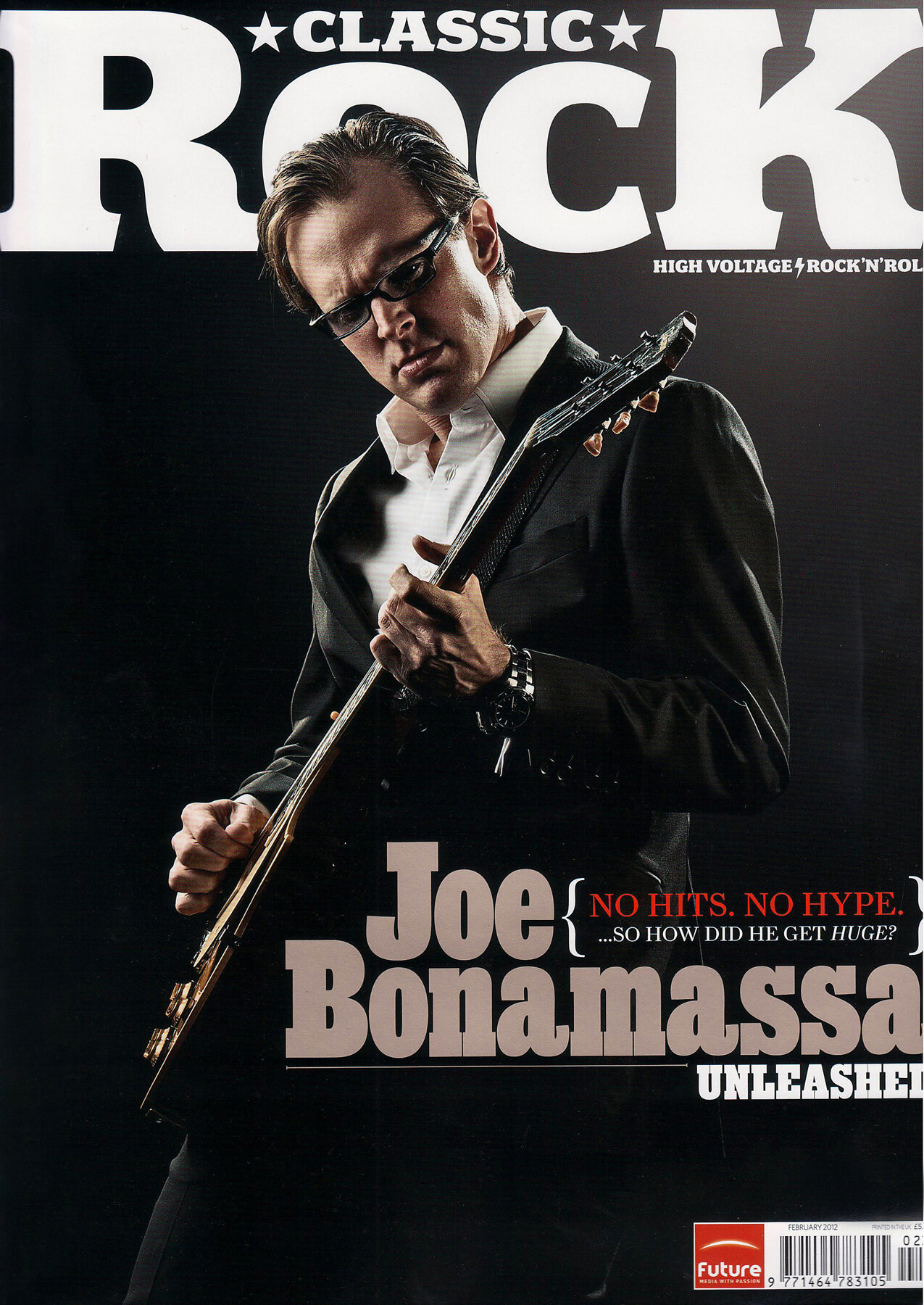

Back in early 2012, I enjoyed a cover story on Joe Bonamassa in Classic Rock magazine. I still remember reading it at the BMV while my son Nicholai was taking his driving test. It focused on the strategy that Joe and his business partner, Roy Wiseman, had followed in charting his career. That part was certainly interesting, but it was one quote in particular that caught my attention at the time and has stuck with me ever since. The heart of the quote was a word of advice from his producer, Kevin Shirley, who said that, “If he wanted to be a blues artist, he should respect the genre.” Here’s the full quote, also describing the upshot:

Kevin Shirley came to see him at a big moment in his career: his first time headlining a House of Blues. “He was overweight, which didn’t bother me,” says Shirley, “but he was dressed in baggy jeans, a dirty plaid shirt, baseball cap and sneakers. Basically what he had been wearing all day, except for the little wraparound sunglasses he wears at the gig.

“I sent him an email saying, ‘Joe, you look like a slob!’ I said that if he wanted to be a blues artist, he should respect the genre – that BB King, and Albert and Freddie King – Muddy Waters and even Howlin’ Wolf and SRV – always looked like they dressed to impress. . . .”

“I took offense,” says Joe. “I go, ‘Kevin, I spent good money on that shirt – it’s Hugo Boss!’ He says, ‘I don’t care – it looks like [crap]!’ Then I got really sick doing a tour in the UK in early 2008. . . .”

He lost 20 pounds in three weeks, bought a nice suit for a gig in Paris and when he saw pictures later, realized that he was on to something. Now he’s suited and booted for every gig. “TJ Maxx is your friend,” he smiles. “There’s a side of you that thinks, ‘Who do you think you are?’ But you look at pictures of Muddy Waters in the 60s and those guys were styled. I always said, I have to be dressed better than the people who come to see me.” (Classic Rock 167, February 2012, p. 59)

“Respect for the genre” includes a variety of things, to be sure. It begins with respect for yourself and your audience. It includes respect for the music itself, taking pains with the crafting and performance of the songs (something that is evident across Joe’s thirty-plus albums). And it also requires that attention and respect be given to those who have gone before you, who blazed and paved the trail that you presume to follow. Artistic creativity (and, really, advances in any field) build upon the past and grow from there. There’s a burgeoning number of music genres in our present day and age, and it becomes difficult to define or distinguish the nuances between them. But people know the blues, for example, when they see and hear it; not only by way of the musical technicalities, but by the entire ambience and culture of that genre, by the traditions that are maintained within it.

Well, what is true for a blues man is all the more true for the Lord’s own ministers of the Gospel. They must also “respect the genre,” so to speak, of the Gospel Ministry; not only in the technical details of their various and sundry functions, but in the entire conduct of the Holy Office to which they are called and ordained by the Word and Spirit of God.

If you would be the Lord’s man, respect the genre! That means respecting, not only yourself and the people you are given to serve, but the Lord Himself, in whose Name you are called and sent. Above all, it requires reverence for the Lord your God and for His holy things. It’s no good arguing that “reverence” is ambiguous and indefinable. It is more objective than that, and people know it when they see it (and where they don’t). In its particulars and specifics, it is determined and shaped especially by custom, much like the sounds that make up our words and vocabulary.

To respect the “genre” of the Liturgy (which is the body and soul of the Ministry of the Gospel) is to receive, practice, and hand over the traditions of the Church catholic, as St. Paul argues in First Corinthians 11. Those traditions include, not only the administration of the Lord’s Supper (1 Cor. 11:23–26) and the confession of Christ, crucified and risen (1 Cor. 15:1–5), but also the ordering of men and women under the headship of Christ Jesus within the life of His Church on earth (1 Cor. 11:1–16). St. Paul argues from theology and from “nature itself” that a man should not pray with his head covered, nor should a woman pray with her head uncovered. Significantly, he concludes by pointing out that “the churches of God” have “no other practice” (1 Cor. 11:16).

When St. Paul draws upon the example of “nature itself” in reference to the appropriate length of a man’s or woman’s hair (1 Cor. 11:14–15), he points not to some absolute and universal law of hairstyles, but to the basic human instinct that men should look and act like men, and that women should look and act like women. Despite all recent arguments and efforts to the contrary, people still know what men and women are like, even though particular styles have certainly changed in the course of history and across a variety of cultures. To “respect the genre,” likewise, honors the fact that changes and developments over time do not undo the fundamental point and principle that churches ought to look and act like churches. And that doesn’t start from scratch.

To “respect the genre” of the Body of Christ is to respect those who have gone before you, as well as those who serve alongside you in the present, those you are given to serve in your own place, and those who will follow after you in due season. That is to say, honor your fathers and mothers, love your brothers and sisters, and care for your sons and daughters in the faith. To do so is more than following the minimal “letter of the law” in respect to liturgical practice. It is to humble oneself in submission to the Church and Ministry of the Lord who calls you to serve His people with His holy things. As the Gospel itself did not originate with you and does not depend on you, neither do the ceremonies and customs of the Church belong to you and your whims.

Certainly, “adiaphora” are by definition free and therefore subject to change. Nevertheless, the actual use of adiaphora in practice does communicate, confess, and catechize within a larger and ongoing context. Just as the verbal sounds that make up the words of any language are free and subject to change, and yet they bear the meaning assigned and agreed upon, so do people identify and interpret various ceremonies (pro or con) within the continuity of a conventional consensus. People know what the Church looks like because “the churches of God” have been doing things with a high degree of consistency and stability for many hundreds and hundreds of years. It’s not that nothing ever changes, but the more sudden and radical the changes, the less recognizable the Church.

Contentious innovators may argue that all the necessary technicalities are still retained and done correctly, with sufficient precision (a debatable point); but where the accouterments, adornments, and accompanying ambience (whether simple or elaborate) are abandoned and fail to “respect the genre,” the heart and soul of the matter will also suffer abuse. It is not unlike the argument that St. Paul makes regarding meat sacrificed to idols. While you may be clear and secure within your own conscience, your outward actions nevertheless convey misleading implications when you jettison the commonly accepted customs of the Church in favor of your own creative style.

Those who argue that the Word and Sacraments are sufficient of themselves, and that we can neither add anything to them nor improve upon their efficacy, are correct to that extent, on the surface of it. But they contradict and undermine their own argument when they do not honor the Word and Sacraments with reverence as divine works and holy gifts. What is more, in acting as though the Word and Sacraments will simply “do their thing” regardless of how they are handled or (mis)treated, they operate with an extreme “ex opere operato” attitude, which presumes upon the Lord and dishonors His authority and freedom to do as He will, “where and when it pleases Him.” It is not that any of the Church’s adiaphorous ceremonies contribute anything to the efficacy of the means of grace. It is only that reverence for divine and sacred things must somehow be confessed and outwardly expressed, and to do so requires the use of a readily recognized “language” of action.

The Lord is to be sanctified in the presence of His people (Lev. 10:3), especially in approaching His Altar and in the handling of His holy things. Such reverence for the Lord belongs not only to what is said and done, but so also to how it is said and done, to the way one carries and conducts himself in the presence of the Lord our God. Our safety and security are surely not to be found in the human customs and traditions of the “genre,” but solely in the Word and promises of the Gospel of Christ. But we honor and give thanks for the grace of His Gospel in ways that are recognizably reverent, rather than insisting on our own casual comfort, cleverness, pleasures, and preferences.

Music can be captured and shared in all kinds of ways and by all sorts of media these days, but there’s still nothing else that competes with or compares to a live performance. In such a case, it is not only the musical sounds but the entire show that communicates and conveys the artist himself along with his art. That will be done, either with a recognizable “respect for the genre,” or with personal hubris and an obvious “contempt for the genre.” That is true for the blues as a musical genre, as it is for classical ballet and for any other established art form. It is certainly no less the case in the conduct and administration of the Liturgy, which is necessarily “live” and “in person,” and which does not happen in a vacuum but within a large and living context (whether in continuity or conflict with it).

As surely as I know what to expect from Joe Bonamassa this evening — that he will ply his craft not only with consummate skill but with a consistent respect for the genre — so should we all be able to rely upon the ministers of Christ to administer His gifts with competence and reverence. “But if one is inclined to be contentious, we have no other practice, nor have the churches of God” (1 Cor. 11:16).